ON THIS PAGE:

1. MODEL TRAIN INTRO

2. BIRTH MOTHER – AN ANSWER

3. LETTER AND ESSAY INSPIRED BY VACLAV NELHYBEL AND AN INSTRUMENTALIST MAGAZINE REQUEST

4. ESSAY – (CONCERT BAND) “THE LIST”

5. ESSAY – “WHAT DO I SEE…”

6. ESSAY – “NOT WHAT I THOUGHT I WOULD BE DOING…”

7. SOUSA STINGER EMAIL ANSWER

8. ESSAY – “HOW DO I LEARN TO ORCHESTRATE?”

8A. ESSAY – “HOW DO I BECOME A BETTER MUSICIAN?”

9. ESSAY – SUMMER OF 2012 / PHI MU ALPHA SINFONIA

10. ESSAY – FACEBOOK, 2014 – ON CONDUCTING

10A. A CONDUCTORS RANT: OPINION ON NEW BAND MUSIC

10B. MY PERSONAL GUIDE LINES AS A TEACHER/CONDUCTOR

(ADVICE TO YOUNG TEACHER/CONDUCTORS)

11. BOOK EXCERPTS (FOR STUDENT RESEARCH – IN BLUE TYPE)

****

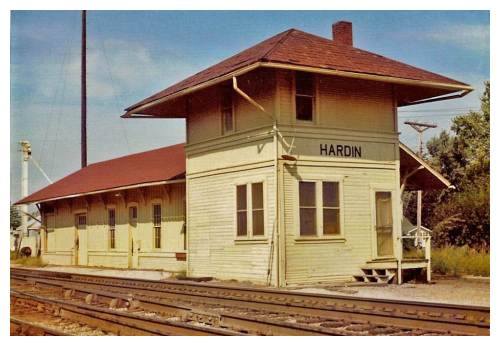

1. THE “ANY TIME ANY SPRING” MODEL TRAIN LAYOUT

I play with trains.

There, I’ve said it. I’m not interested in prototypical railroading. I don’t do any that stuff that “real” model railroaders do, and there’s a reason for that.

I grew up in a small town in north central Missouri. The main Santa Fe and Wabash lines between St. Louis and Kansas City ran right through the middle of my little farm community. On those four tracks, over 85 trains a day barreled through town when I was a kid. (I understand that there are still a large number traveling those tracks even today.) I lived on a farm a mile from town and from my upstairs bedroom window I watched as those freights and passenger trains of the 50’s and early 60’s roared across the countryside just a half mile from my house, morning, noon, and night. My Grandmother’s house in town was less than 50 yards from the tracks. When the trains sped through, the whole neighborhood shook.

I remember watching the trains “catch” the mailbags at the depot.

I remember two sensational head-on train wrecks in the middle of town during my boyhood years, both caused by work trains pulling out too early onto the main line and meeting head-on with a thundering freight train once and another time with a mail train. I recall that the mail train was full of uniforms for the Air Force Academy and the track was littered with blue overcoats for weeks during the cleanup. I know the work train guys jumped to safety, but both the engineers were killed, one, I understand, making his final run before retirement.

Anyway, I never watched a “yard”. There were no industries around Hardin, Missouri, unless you counted the sidings to the grain elevators.

So, to this day, I just like to watch the trains run. And that’s the kind of layout I like to build. Lots of curves, grades, and straight-aways with a multitude of different trains all running through the scenes. I sit at different spots around my layout, sometimes on a high stool looking down on the action and sometimes at eye level, just to watch the trains roll by. So, all you “real” train guys can shake your heads sadly and say, “What a pity this guy isn’t really one of us”, but the college students who come over to see the layout don’t care, and my grand children REALLY don’t care, so I’ll just keep contentedly doing what I do, enjoying every moment.

I play with trains.

*****

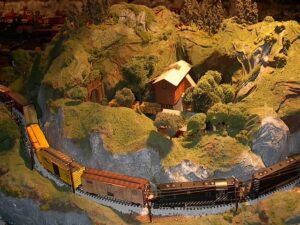

I had a medium sized L-shaped (“traditional” 4X8 by 4X8 plywood sheets) model railroad layout in our last Texas house and when we moved to Tennessee in 1999, my wife was adamant that we find a house with a basement so I could build a new layout. After-all, it was a hobby that kept me “out of the bars and off the street” – not that that had ever been a problem before. She just was very aware of how much I enjoyed something that was different than the musical life I lead.

The first year at Lee University seemed so busy that I didn’t really get a fast start on the new layout. My children, aware of this, gave me LUMBER for Christmas! It was somewhat a declaration for Dad to get back to that “fun” thing he enjoyed.

The first “Tennessee” layout was simple. A “stand in the middle” rectangular “duck-under” layout about 10 feet by 12 feet in diameter. This “box canyon” layout was built and lasted about three years, when I realized that I was building inward at such a rate that I wasn’t going to have room to stand inside much longer.

That first un-named pike was torn down and building began in earnest in the fall of 2003 on a much more expanded layout that eventually turned into a large capital “J” layout that covered an area about 12 feet wide and 21 feet in length. It was aptly named the “Any-Time-Any-Spring-Run-Any-Engine-I-Want-to-No-Matter-What-Era-Because-It’s-My-Table-And-I-Built-It-And-I-Can-Do-Whatever-I-Want-to” HO Train Layout, because . . . . well, I don’t necessarily stay in a designated time frame very well. I’m not a steam guy. I don’t really go for modern railroads. I tend to like the trains I grew up with. All the diesels with double trucks. F units and Geeps. Santa Fe, CB&Q, and Missouri Pacific lines. Older 40-foot boxcars. Trains with CABOOSES!!!! (You can find that older website by going to www.davidrholsinger.com/trains and there is a tab to a previous website.)

I kept a running dialogue and picture diary of that railroad, later shortened to “Any time Any Spring” (ATAS) layout on my previous website. The final pictures of its construction were posted in November, 2009. For the next two years I ran trains on that pike. In the fall of 2011 I torn it down and began drawing plans for a new expanded version that I assume will probably be my last layout.

And in the end . . . .

****

2. LOOKING FOR BIRTH MOTHER – AN ANSWER

Upon moving to Tennessee some 25 years ago, I decided that I should at least attempt to find out who my birth parents were. Of course, the first avenue was to hire one of those adoption detective agencies in Florida who advertised overwhelming success. They took my money. And six months later, when I called them back, I was informed that Missouri adoption files are closed and their search had been fruitless. I knew that – I just hoped they had other avenues, no matter how clandestine. Since THEY didn’t call ME back, I pretty much assumed that my file was “lost” in the shuffle.

They didn’t offer to give me my money back.

I did a little searching on my own in Jackson County, Missouri, courts and did discover some information. And until now, the following statement has been on my website:

I was born on December 26. 1945, in a hospital or a home for unwed mothers in Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri to a 20-year-old girl who I believe was named Betty Dier. At the time of my birth she was 4’10” tall, weighing 103 pounds with blue eyes and brown hair.

(This name appears on a court document changing my birth name that I discovered in my parents’ lockbox following their deaths.) I was originally named Darrell Dier. (I have no idea how they were permitted to keep such as informative document.)

According to other court records I have been able to obtain, my birth mother’s family was of German descent. Her father worked on the railroad. She had 4 brothers and 5 sisters and at the time of my birth, she was a supervisor in a tabulating department of a publishing company. I do not know where she lived, but there is some hearsay evidence of either northwest Missouri or southern Iowa, but this may not be factual.

If she is living, I expect nothing from her. I simply wish to assure her that she made a good decision those many years ago. I was raised by wonderful parents and have had a successful and happy life. My hope is that her life was just as blessed.

I obtained this information from what appeared to be an exit interview before my birthmother left the Catholic Birthing Home to board a train at Union Station and return home. A genealogist in Kansas City, who has become a very close friend, took up my case as a hobby and begin to dig into this information. As it turns out, of course, much of the information taken in the “exit interview” was not exactly accurate. Interviewers were tired and overworked and many times just not interested in accuracy. Names are misspelled. Family information misconstrued. Lots of mistakes.

I finally ordered a DNA test from ancestry.com. This test did have enough markers to start identifying the maternal family. I don’t know what genealogists actually do, but my gal poured through hundreds of public records, census records, railroad records, and even military records, and did indeed locate, without a doubt, my birth mother in a state far removed from Kansas City.

I had always assumed that my background was mostly German, even before finding this ancestry information. Surprisingly, the ancestry.com result showed the biggest percentage of my DNA was Irish! I was able to take a more extensive DNA test, with some 47 markers and that began to lead to this post I made on Facebook in the spring of 2017:

I HAVE LOTS OF NEWS concerning my search for my birth mother and father. Because of privacy matters I shall not give names, however, with the help of a wonderful genealogist in Kansas City, we have burst through all the misinformation on my birth and adoption records and through extensive DNA research, I not only know the name of my birth mother and birth father, but I also have photos of each as they appeared in 1945. She appears to be a vivacious dark haired beauty and the photo of him is a dashing young Army enlisted man.

They are both deceased, which should come as no surprise. She passed away in 1997 and he died in 1981.

And not unexpectedly, there was an overwhelming response to that post, to which I posted this answer:

I appreciated the many heart-felt comments to my post concerning finding my birthparents. Many people who have completed the same search related stories of reunions with prior unknown relatives. Many asked if I had such plans.

And although it may disappoint some, my answer is………no.

I really am not interested in finding “Lost” relatives. I already have some dear relatives. I don’t really need any more new ones! LOL.

It is just something I have wondered about – who, what, where, etc. Just knowing is enough at my age. I have no urge to search any deeper. Just knowing who my birth parents were…… is enough.

My birth mother married some 10 years later and had three children from that union. There is a likelihood that that new family knew nothing of my birth. In fact, many times the birthing centers in Kansas City told the mothers that their infants had died at birth. There is the possibility that my birth mother didn’t know that I ever existed. Why would I want to open a can of worms at this point? She is deceased. But I know her name, and that is enough.

My birth father was the serviceman. Frankly, I don’t know if I was the result of a lengthy relationship, or, to be blunt, a one night stand. He may not even know there was a pregnancy. I know his identity because of specific DNA results. Again, at this juncture, I have no compulsion to locate distant family members.

I have a family. I am David Rex Holsinger, son of Marvin and Hannah Holsinger of Hardin, Missouri. I’ve stuck with that name for 77 years. Why would I want to learn to spell another name at this point?

Marvin and Hannah Holsinger are buried side by side in Hardin, Missouri. They are the people who led my heart to life and music. I will forever be grateful for their love.

****

3. LETTER AND ESSAY INSPIRED BY VACLAV NELHYBEL AND AN INSTRUMENTALIST MAGAZINE REQUEST

MY RESPONSE TO AN INSTRUMENTALIST MAGAZINE QUESTION

CONCERNING PERSONAL HIGH POINT IN THE MIDWEST CLINIC FOR

YOU…..(PUBLISHED IN NOVEMBER, 2016 EDITION)

My most memorable experience from the Midwest Clinic actually had its roots in an event that occurred in my college years, particularly 1966, and culminated in one 15-minute conversation in the exhibit area of the Hilton Hotel in, if memory serves, 1994.

Like a number of small colleges in the Midwest, the Central Methodist Band always had a spring tour, usually consisting of seven days of travel with three concerts a day at schools or churches. In the fall of 1965, our band director announced that we would have a guest composer traveling with us on the upcoming spring tour. His name was Vaclav Nelhybel and he would be conducting two of his recent works, Trittico and Chorale.

Two days before tour, Vaclav Nelhybel walked into our band hall, stepped on the podium, lifted his arms . . . And as I watched that first slashing downbeat of the baton, I had my very first realization of how “personal” music could be. In that one electrifying instant, I saw brutality, beauty, angst, anguish, joy, triumph, sorrow, exhilaration, devastation, despair, hope, faith . . . all in the eyes of one man conducting HIS music. At the close of the final tour concert, I was overcome by the transformation I knew was happening in my life. I had now come face to face with my future. I wanted to be a composer.

Fast forward to 1994. Standing in the lobby of the Chicago Hilton, visiting with my friend, Tom Stidham from the University of Kansas. Tom interrupts our conversation with “There he goes…” I turned to see the flash of white hair disappear around a corner and ask, “Who?”

“Nelhybel.”

My first thought was to run through the crowd, throwing people helter-skelter, hoping to have at least one small conversation with this man, who had 30 years before, changed the entire path of my life. Not unlike many others, I’m sure. But he was gone.

That night, I lay in bed, quite aggravated with myself, knowing that since I am stuck in exhibits all day, there is little chance that I would get to see or meet with him.

The following morning, I am in the TRN Booth, at the far end of Aisle 3, with my publisher, the late Pete Wiley, preparing for the “opening bell”, if you will. I volunteered to Dr. Wiley to step away and go get us a couple of cups of coffee. I step into the aisle, and what do I see? Vaclav Nelhybel is standing at the other end of that exhibitor’s corridor, people zooming to and fro around him, like one of those surrealistic movies where everyone else is a blur, and he stands there, the only clear and visually dimensional person, breathlessly waiting for someone, anyone, to pull him from the barrage of swarming motion surrounding him.

I’m sure I said a quick “Thank you Lord” under my breath as I hurried up to him. I fumbled through some inconsequential facts about where we met, and how much I appreciated his music, how much of an inspiration he had been, and then finally, almost as an afterthought, I began to introduce myself. He interrupted my babbling, saying, “I know you. You are Holsinger, the famous composer.”

I’m not sure what happened in that split second. There’s a good possibility that I levitated at least four inches off the floor. He then proceeded to tell me about the teacher in his life that had fired his young passion to composition. Then with an off-handed admonition to “pass what we do on”, he turned and walked off, swallowed by a suddenly awakened crowd of admirers at once aware that he was standing there in their midst.

I never saw him again that week. Within a year or so, he had passed away. I know that in that point of the century I was not the only person changed and challenged by this incredible personality. But I do know, that those heady days in 1966, and that 15 minutes in the exhibit hall of the Midwest clinic have shaped, to a great degree, my life long desire and responsibility to “pass it on.”

Epilogue

What did I learn about the “Nelhybel style” during that week that has colored not only my performance of his music, but also my own composition? For one thing, his music seemed to be the very opposite of what I had always been taught to think.

You must remember that it was 1965 and for the most part, we were all being “traditionally” taught about the sensitivity of music and the proper way to treat phrasing, melodic contour, and musicality in general. I still teach those musical attributes from the Vandercook book of 1926, “Expression in Music”. Those attributes are still a primary process in performance technique to me.

Most of the music that I confronted as a young musician in band in the 1960s was not only composed to fit that mold but it also was guided by those performance practices.

We didn’t overblow. We rounded off our phrases. We lifted gently the ends of our crescendos. We were very obvious of playing with a “blended sound”, no timbre really “sticking out” of the instrumental pallet, always careful that the “true band sound” was that of a great cathedral organ. (I suppose I should have known better, when I discovered that Stravinsky referred to the organ as “the monster that does not breathe”!) but this was the criteria my conductors always adhered to, and was traditionally the sound associated with my college band for decades.

And then, there is the “contrary to the rule.”

There was Vaclav Nelhybel.

Perhaps the best word I can attributed to his sound is not aggressive, but rather AGRESSION! He demanded more from his music. His softs were not soft enough. His fortes were not loud enough. His crescendos were, in a word, vicious.

I think the first thing he did in rehearsal was the to force us to play beyond the end of the crescendo, and basically “rip” the release. Totally the opposite of what we were taught.

He demanded we push the air at the end of a crescendo. Actually “flare” the sound. (You begin to realize that this flared push is expected anytime there is a pitch tied over to an eighth note, for instance.) In his notation, he always indicated exactly where the crescendo comes to an end, by writing an actual note the pitch is tied to.

Ha! The concept of “blended sound” went out the window with his music. Brass players loved it! But he also demanded that same aggression from the woodwinds. And the percussion? No longer did they live in a world of ratty-tat-tat, but suddenly they were a driving machine of thunderings and poundings. (definitely a foretaste of what the modern percussion section has become!)

Because it is a simpler piece, I would occasionally take FESTIVO out on Honor Band performances. I would of course teach the students the “Nelhybel style”. The old-timers would invariably congratulate me on playing Nelhybel as it “should be played.” However, and this happened more than once, a young band director would tell me that they had tried to play FESTIVO with their group, but found the piece to be very boring. There is a reason for this.

I wonder if the composer needed more instruction to be given to the players with his notation?

It seems the only people who really know how to play Nelhybel are those who sat under his baton at one time or another. Personally, I lay a lot of the blame on lazy editing by his publishing company, Franco Colombo. (Out of business by the late 80s, by the way.)

I was hoping when Trittico was republished by Alfred several years ago, that some smart editor would take the time to “re-edit” the music and add needed nuances. But unfortunately, they simply recopied the original publication. So I suppose, for the most part, the “Nehlybel style” will be a matter of “oral history”, passed from one generation of band director to the next. (I have always attempted to do my part.)

***

4. ESSAY – “THE LIST”

We are a wind band society dominated by THE LIST. We have the ten best, the ten worst, the ten most likely, and the ten least likely to appear on any list whatsoever! Everywhere I turn I am confronted by yet another list of the most important works for conductors to know. Trust me, I’ve seen a ton of them. I have Foster’s “fifteen landmark” pieces list, Stamp’s “If you had to pick twenty pieces” list, Cramer’s list, Junkin’s list, Haithcock’s list, Mallory’s list, and Kirchhoff’s list. I even have a four year old repertoire list from Gene Corporon that lists 988 works! Does this mean that now, four years later, I should expect to be confronted with a magnum opus entitled, “The 1500 Greatest Works for Winds and Best Restaurants in North Texas?”

And now, I have been asked to list ten works I think band conductors should study. I’m not sure I have the expertise to write such a list. True, I’ve been conducting for years, but 50% of that has probably been my own music. I haven’t been a university level conductor all that long. Consider this. In 1999, most of my 1967 college classmates retired, and I moved to Lee University to begin, in most people’s opinion, my first REAL job! To be perfectly honest, I’m still working on EVERYBODY ELSE’S list at present!

I will say one thing about the importance of all these lists. The wind band area is the most volatile area for the creation of new music in the world today. This is wonderful news for composers and conductors alike. However, it does breed in us, a certain laissez-faire attitude toward the music of the past. We tend to forget our foundations. We tend to forget the masterworks that put us on this popular plateau in the first place. We tend to leave behind the landmark works of the past decades, in order to always be on the cutting edge of NEW. The FRONT BURNER seems to dominate our choices, even when the newly touted young composer’s ingredients don’t really make a very edible musical meal.

Lists keep us honest unto ourselves. They ensure that we will not forget the Persichetti’s, the Hindemith’s, the Schoenberg’s, the Schmitts, the Hartleys, the Holsts, the Graingers of our recent heritage or the Ferdinand Paers, the Franz Krommers, and the Rimsky-Korsakovs of our distant past.

Let’s be choosy when it comes to lists.

***

5. ESSAY – “WHAT DO YOU SEE?…..”

“As a composer, what do you see as the future of band music?”

“As a conductor, what do you see as the future of band music?”

I’ve been asked to address this question on several occasions, and although I’m sure I articulated golden hyperbole about the “American Ensemble” – because I’m a certified band nerd – I’m convinced that ONE primary path, among the hundreds of tributaries, in this “future of band” issue boils down to composers and conductors and HOW EACH RELATES TO THE OTHER. But, to examine the FUTURE also compels an examination of the PAST.

I had a composition teacher who said, “Composer’s ears are 20 years ahead of listener’s ears and ten years ahead of most conductors.” He was certainly on the mark if we are to consider a past century of new works and their history of ACTUAL acceptance. After all, look at the progression of schools of composition in the 20th century! We hardly had time to breathe between them, much less absorb them as they, retrospectivally speaking, streaked by . . .

Objectivity, Primitivism, Nationalism, Futurism, Gebrauchsmusik, Satirical Music, Machine Music, Jazz, Neoclassicism, Atonality, Serialism and on and on . . . Wasn’t the premiere of Rite of Spring Booed? . . and 10 years later, it’s “old hat” because now we’re dealing with Schoenberg’s pandiatonic works . . and no sooner did Webern and Berg exhaust that run then we’re confronted with Messiaen’s Modes of Limited Transposition . . . and then Aleatoric music . . . the avant-garde . . . the reactionary 70’s in general! . . microtonal music . . electronic music . . sound mass and sonic clouds . . . and I suppose, at the close of the century, minimalism, where one does as much as possible with as little as possible for as long as possible in order to irritate the audience as prolonged as possible . . . and ten years later, that’s already “old hat” . . .

How can we possibly keep up? It’s a mismatched generational thing. Composers look ahead, and conductors, by the nature of their education, have been more comfortable looking to the past.

I think that in the BAND WORLD however, that “Wide Divide” is closing at a rapid rate.

In his foreword to Tim Salzman’s A COMPOSER’S INSIGHT, VOL. 3, Pulitzer Prize winning composer John Corigliano writes, in a rather biting indictment that, due to the inability of the typical PROFESSIONAL orchestral conductor to understand and teach new music and the PROFESSIONAL orchestral player’s less than stellar understanding of anything other than standard notation, it is (quote) “the orchestral profession that has made itself increasingly inconsequential to the [new] music of our time; and in brilliant and inspiring contrast, there now stands the modern concert band”(un-quote). For band-nerds who need a ego-boost, this one page essay is worth the entire price of the book!

Not demeaning “Universal Judgement”, the American march heritage (I play a Sousa march on EVERY concert – don’t get me started on Pop Tunes for Band!), and the band music of Gustav Holst and Vaughan Williams, I usually refer to the 1950‘s as the opening decade of the “modern” band era. And it really has nothing to do with the formation of the “Wind Ensemble”, per se, it’s simply a mark in the middle of the century when I believe the great divide between the new modern band composer and the band conductor first became evident. It has everything to do with the fact that for the first time in history we had composers who ACTUALLY WANTED TO WRITE NEW MUSIC FOR BAND and conductors on the school podiums who were ill-equipped to deal with that onslaught.

True, when young Frederick Fennell sent out that infamous letter about his new ensemble to 400 composers, he really only received responses from a hand-full. But Look who answered. Grainger. Persichetti. Mennin. Hanson. Not a bad start.

I had as my high school band director in the late 1950s, a man who was trained by a college conductor who was raised in the tradition of the “transcriptions” of the 30’s and 40’s. My college band director in the early 60s was raised in the traditions of the late 40’s and the early 1950’s . . Those who were conductors in the 70’s actually had their roots in the music of the late 50’s and early 60’s . . and on and on.

The problem arises in that the composer in the 1970s, for instance, was writing music OF THE 1970s and not music from the 50’s. He needed a conductor WITH A 1970s MUSICAL MENTALITY as a partner. Unfortunately that very seldom happened in those years. Because of a 10 to 15 year “creativity gap”, the first aggressively modern music written for band many times went begging for advocates on the podium.

In fall of 1979, Robert E. Foster at the University of Kansas asked me to write a piece for his band that would be premiered at the national MENC convention the following spring. I wrote THE ARMIES OF THE OMNIPRESENT OTSERF. It contained diagrammatic notation, time signature-free sections, sonic clusters, aleatoric sections, vocal permutations, box-music, and exotic percussion. The score was, to say the least, unconventional looking. When I first presented the work to Mr. Foster – to say that he was somewhat hesitant to except it is probably a huge understatement. I’m sure that Bob Foster would tell you, if you asked him today, that he had never considered a BAND score quite like it before. But I convinced him of its worth and the piece went on to become one of Bob Fosters conducting milestones. But for him to accept the piece, he had to resist our composer/conductor generational mismatch. He had the authority to veto this piece, but he choose to be a “then and now” conductor!

OTSERF went on to win the Ostwald and I feel that in part, it’s acceptance by the American Bandmasters Association also opened the door to other BAND composers, writing with the same contemporary notational devices, to be gradually accepted by a few BAND MUSIC publishers.

I tell the story because, at the same time I was defending that score across Bob Foster’s desk, in the corner of his office was a two foot high pile of scores that had been sent to him that contained many of the same future-looking notational devices we were discussing. But those scores were not a part of Mr. Fosters “conducting environment” at that time. It wasn’t Bob Foster’s fault nor the composer’s fault . . it was simply a generational mismatching between two EQUALLY important aspects of music performance – the conductor and the composer. (Admittedly, let’s also realize that in that two foot high pile of scores, none of those pieces had a composer advocate standing across the desk from the conductor fervently declaring the worth of these new compositional techniques. Techniques, that unfortunately at the time, were only “new” to the band world, having been explored in chamber and orchestral works.)

I’ve been blessed with “then and now” conductors all my life. In 1965, my college band director at the time, Ken Seward, invited a virtually unknown composer named Vaclav Nehlybel to our campus where our band played his TWO published works, CHORALE and TRITTICO, and my life was changed. In 1966, my new band director, Joseph Labuta decided to program a new piece, PRELUDE AND RONDO, written by the little guy in the baritone section and my life changed. At Central Missouri State University, my band director, Russell Coleman readily programmed “modern” compositions, became a lifelong supporter of my music and my life changed. And Bob Foster, stepped out from a comfort zone in 1979, and introduced an Ostwald winning composition to the public, and my life changed.

In the band world, this great divide between the conductor and the composer is disappearing at warp speed! There is a new generation of conductor and teacher, both college and secondary school level, who are conscious of “what’s on the front burner”.

I am reminded of a story Frances McBeth once told me. As a young composer he was writing work after work for orchestra and getting no takers. His friend, composer Clifton Williams chided him one day. “Frances. Write for Band. That world is crying for new music and you’ll ALWAYS get it played!” That advice is still good.

“Information supply.” That’s a term I’ve been hearing for decades concerning how new music is defined. In this information age of IMMEDIACY, I think the generational gap between the conductor and the composer is being readily narrowed. Corigliano points out in his essay that, unlike the present orchestral culture which tends to continually rehash the greatest hits of the two-and-a half centuries prior to 1900, the culture of the band encourages new repertory, new notations, and new techniques. He also is quick to point out that (quote) “the conductors of today’s bands are always teachers first!” (un-quote)

But playing my own conducting devil’s advocate, I would venture one note of caution.

Years ago, on a CBDNA Panel discussion, Larry Sutherland, retired director from Fresno State issued a warning that we, as conductors, need to be the “filter for the next generation” when it comes to our choices in literature. In this age of immediacy, that musical comfort gap of 20 creative years has all but disappeared. Our choices, as conductors of new music, are becoming ever more critical to the future of our ensemble. The fallacy of that statement is that all of us don’t have the same taste in music. On the other hand, the good news is – all of us don’t have the same taste in music! Unlike the orchestra, the band does not rehash a 200 year old repertoire over and over. If we are guilty of anything, it may possibly be “new music overload”!

The wind band area is the most volatile area for the creation of new music in the world today. This is wonderful news for composers and conductors alike. However, it does breed in us, a certain laissez-faire attitude toward the music of the past. We tend to forget our foundations. We tend to forget the masterworks that put us on this popular plateau in the first place. We tend to leave behind the landmark works of the past decades, in order to always be conductors on the “cutting edge”.

As the “filter for the next generation”, let us be sure to balance our musical palettes. It’s a compositional rule – there is always a need for the proper balance of dissonance and consonance in every piece. That applies to our program choices as well. Let us as conductors be sure that our ensembles feast on a healthy balance of old and new. For the sake of our student musicians, and our listeners, let’s insure that we will not forget the Persichetti’s, the Hindemith’s, the Schoenberg’s, the Schmitt’s, the Hartley’s, the Holst’s, the Gould’s, the Grainger’s of our recent heritage or the Ferdinand Paer’s, the Franz Krommer’s, and the Rimsky-Korsakov’s of our distant past.

What do I see as the future of band music? Hopefully, I see us being . . very careful to keep our balance. Too much dissonance, and we may self-destruct. Too much consonance, and we become some kind of musical “warm gravy” ensemble. We have a gift for the listener the orchestra does not have, but it is essential that we project all of our diversity to the audience AND to our student musicians, who will become the NEXT GENERATION of conductors and “filters” of music.

There’s my answer. But I still hate this question.

****

6. ESSAY – “NOT WHAT I THOUGHT I WOULD BE DOING…”

It was almost alarming how many emails I received from supervising teachers following an interview several years ago in the INSTRUMENTALIST concerning “inexperienced” student-teacher conductors and their lack of “fix-it” knowledge. A number of the writers mentioned that their student teachers admitted that, although they knew something was wrong in the music they were conducting, they couldn’t figure out what it was or how to address it.

That is somewhat of an indictment on two fronts. First, we who teach those young conductors are obviously missing something in our methods. And those young conductors, who sit in our ensembles day after day as playing musicians are not paying attention! Or at best, they are not realizing that all that is being poured into them day after day is meant to be musically articulated and poured back out on others in the future.

Admittedly, most student teachers go out with only two semesters of classroom instruction in “conducting” as part of their degree program. In some smaller colleges, there may be only one class of conducting offered. Unless the students get to conduct in some regular arena on campus, there’s only enough time to teach the basic patterns and “book” gestures in one semester. Of course, there is a wealth of conducting “tips” found daily in professional magazines and on the internet that deal with the “artistry” of conducting. But I think the alarm I hear from supervising teachers is not concerned with knowing a beat pattern, or how “pretty” they look in the execution, but rather with knowing how to think and express to young musicians the essence of musical expression.

I am constantly encouraging, most of the time literally demanding, that my musicians develop fundamental truths about music. That each of them develop a “belief system” about specific aspects of music. Obviously I believe that being a conductor is more about being a “teacher” than being an “artiste”!

And yes, I am assuming that the teacher has taught the foundations of the physical aspects of playing an instrument. And yes, I am assuming that the ensemble is past the point of “right notes in the right places” in their musical journey. What I am concerned about is the young conductors lack of “personal musical and expressive attributes” that they REALLY believe are essential to producing fine musical moments.

Admittedly, every conducting class suffers the mass of handouts detailing the “facts” of conducting. I have several that I have collected over the years – one with 28 separate items and sub-items, another with literally a different list of 38 “a conductor should…” items, and a final list of 11 “functions of a conductor” that I borrowed from a colleague I respect. The problem with “facts” is that, unlike the music history exam on tropes and lauds (and no offense to musicology buffs in the audience), just regurgitating the facts on the final exam doesn’t close the door on your “commitment” with that subject

When I arrived at Lee University in 1999, I assumed that I was there primarily to teach young composers. I was wrong.

I was there to teach the future of our profession. Winona and I were there to insure that all our young conductors and teachers walked into their first jobs musically armed and dangerous! That each young charge left our classes with more than a beat pattern and a couple of fancy moves. That each conductor left us with a MUSICAL BELIEF SYSTEM. That each young teacher left with concepts about line, and texture and contour and all the attributes of expression firmly ingrained in them. Almost religiously! So that when they stepped in front of their first ensemble there was not that cloud of anxiety shouting “What the heck do I fix!?!” but rather they stand confident saying “These are the ways of music. Let me take you for the ride of your lives”!

I think the primary role of my life now is all about the teacher/conductor.

****

7. AN ANSWER TO AN EMAIL QUESTION TO THIS “EXPERT” CONCERNING A YOUNG BAND DIRECTOR’S INQUIRY ASKING IF THE STINGERS WERE OPTIONAL ON A J.P. SOUSA MARCH. REALLY!?!? WHERE DID THIS GUY GO TO SCHOOL!?!?

I’m not sure about the “expert” part, but I do enjoy playing Sousa marches. I once had a teacher who told me, “If you can play a [Sousa] march musically, you can play anything musically” – That was his exhortation to me not to “dismiss” the importance of the American march.

One of the keys to playing a Sousa march correctly, at least to me, is being very concerned with the bass drum. (When Sousa guest conducted, he was always accompanied by his OWN bass drummer.) I think this concern is due to his fascination with the “two-step” dance of the turn of the century. It was a dance with a heavy beat one and a light beat two.

So here is my first rule of Sousa:

It doesn’t matter whether you are playing one of his “horse parade marches” (6/8) or a Regimental march (usually contains trumpets on separate bugle-like parts) or one of the “dance” marches (Manhattan Beach, Stars and Stripes, etc.), UNLESS OTHERWISE MARKED, THE BASS DRUM SHOULD ALWAYS BE PLAYED STRONG FIRST BEAT OF THE MEASURE, LIGHT SECOND BEAT. (This will change the feel of the march remarkably!)

[Let me add at this point, that others may not agree with this idea. It is educated historical conjecture on my part, and may be completely wrong. However, it serves the music well and I’m too old to change my opinion now!]

The question of the “stinger” is not whether you play it or not, but rather HOW LONG IS THE NOTE. If it has a stinger, it HAS to be played. I’m not sure why you raised the question, to be perfectly honest. If Sousa wrote a stinger, I can’t imagine that he considered it “optional”.

The issue is this – a “putt” is not a note. A note should be long enough to establish tonality. You have to be careful with that “house-top” accent (^). In today’s notation practice, that mark usually means a very short punched note. However, at the turn of the century it was simply a louder accent than the marcato accent (>). Not shorter.

So basically, I make it a practice to play the “stinger” full value. (If it’s a quarter note in Cut-time, that’s a HALF OF A BEAT. – not a sixteenth “putt”.) Anyway, the issue is that it has to be long enough to establish a strong final tonality point to the piece. This is just MY OPINION. I’m sure there are as many different ideas about the length of a “stinger” as there are stingers to be played.

If there is a heritage to the American Band, it is the “American” march form. I encourage you to make it a major part of your band’s education. Lady GaGa tunes will disappear in a few decades, but Sousa, Fillmore, Karl King and friends, will be with us always.

****

8. ESSAY/E-MAIL ANSWER/YOUNG PERSON ASKING “HOW DO I LEARN TO ORCHESTRATE?”

Thanks for your email AND an easy question to answer. You cannot imagine how many requests I get, usually from high school or junior high kids, asking me how to be a good composer. Most of them want to be famous overnight. Unfortunately for them, it’s a lot easier task to be a bad composer than a good one and most of them don’t have the wherewithal to face the trials and tribulations it takes to be successful at the craft of composition.

When I was young, a million years ago, there was an abundance of books concerned with arranging and orchestrating by various composers in Hollywood. The books told you how to orchestrate your music so you could SOUND JUST LIKE Henry Mancini, for instance. Or Russ Garcia. Or John Cacavas. Those books are probably still out there somewhere. But why would I want to sound JUST LIKE those composers?

I think the best “textbook” on orchestration is the book “Instrumentation and Orchestration” by Alfred Blatter. But any textbook is simply a manual on the instruments. It helps you know the instruments. However, when scoring your music, it’s almost better to know what the instrument CAN NOT do, rather than what it can do in the hands of a good player.

I had a composition teacher once who told me that when you orchestrate your music, you’re actually re-composing. Adding color to the notes. Makes sense to me.

When I started composing, basically all composers would orchestrate in “families”. But in today’s new world of composition and sound, there is no unacceptable combination of instrumental timbres.

So, my best advice on how to orchestrate is to listen. Find moments and examples in various pieces of music where the orchestration catches your ear. See what that composer did at that moment. Why is the last chord of the Holst First Suite Chaconne such a brilliant sounding simultaneity? I think that’s the greatest chord in the world! (Just my opinion). So how did he score it? Find out, and put that moment in your scoring toolbox and dwell on the properties of the chord. And when you use that voicing, it won’t be Holst anymore, it will be a new version of you. Stravinsky did it all the time. Borrowed ideas from others, put them in his own toolbox, rattled them around, and they reappeared as “Stravinsky”!

I guess what I am saying is, build your own book in your head. Borrow, experiment, learn to erase if it doesn’t work, steal from the best, start with the composers and music you like best and see how they made things sonicly happen.

****

8A. ESSAY: HOW CAN I BE A BETTER MUSICIAN?

ANSWER TO A YOUNG HORN PERFORMER ON HOW TO BE “BETTER MUSICIAN”

How to become a better musician? That brings to mind that old, old, weary joke about “how do you get Carnegie Hall?” “Practice man, practice!”

But if you plan on majoring in the performing arts, particularly on F Horn, I don’t know if there’s any better advice. Our low brass instructor here at Lee University has a plaque on his wall that says “Don’t practice until you get it right. Practice until you can’t get it wrong.”

Also, as a good musician, listen and learn all you can in your chosen field. I don’t know if you feel like you are a “band guy” or an “orchestra guy” in your dreams of performing. Whichever, immerse yourself in whichever area you find the most satisfaction. Begin to establish a “musical belief system” concerning your personal attributes of expression, your personal understanding of your instrument, and where you think you want to be 10 years, 20 years, 30 years from now. And trust the advice of people around you, personal advice, musical advice, and perhaps even spiritual advice

It’s not where we come from – It’s where we dream of going.

I came from a farm town of 600 people and a high school graduating class of 13 – that’s what I said – 13. (9 girls and four guys)! And now I get music played literally around the world. But still, basically I was just a farm kid from Nowhere, Missouri.

But it wasn’t an “instant trip”. I would have liked for it to have been, true. But I had a lot to learn before I could step into the “big time”, so to speak. And the funny thing about it is that my teachers were not famous . . . they taught at relatively small schools, but they were exactly the RIGHT teacher for me at the RIGHT TIME. I didn’t necessarily agree with what they were saying to me when I was sitting in their studios, but as I matured (Thank God!) their words and teaching suddenly took on a new perspective. (Same principle that the older you get, the smarter your parents are!)

My wife and I had these friends whose daughter was an unbelievably good clarinet player in a small-town band program in Missouri. Granted she was more than good, she was gifted. She auditioned for the US Marine Band in Washington right after High School . . . . AND MADE IT!!! But her parents, who were both very gifted musicians and band directors, wouldn’t let her accept the position. They wanted her to go to college. Their position was that if she was that good now, after four years at Michigan, she would be better and would be able to win another spot in Washington. She just finished a career in the clarinet section with the Washington Navy Band for 25 years.

Delay is not Denial.

Sometimes that is God’s plan for our life. When I’ve been in “too much” of a hurry to make things happen, things have not always gone as “I” planned them. Sometimes a little “waiting” is OK.

I must admit that usually letters like yours are from young aspiring composers who want “a quick magical way to be famous overnight!” For them, I have the number of essays on hand from different composers, all of which have the same message: “learn your craft” and “wait your turn”. Those with talent and perseverance will succeed. I suppose that also may be the best sound advice I can give you.

Perfect your craft. Listen and practice.

Admittedly, “hocus-pocus Bobidy-bibbity-boo!” WOULD be easier. But you would have to be a cartoon mouse to really appreciate that.

9. ESSAY – “PHI MU ALPHA SINFONIA. SOMETIMES YOU JUST . . . FORGET . . .”

SUMMER OF 2012

Forty-eight years ago, in the spring of 1964, I pledged Beta Mu Chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia at, then, Central Methodist College in Fayette, Missouri. Every Thursday evening the chapter would meet, in the highest accessible room above the campus, the Tower Room of Linn Memorial Church. I was almost immediately elected as secretary to the group and served rather bombastically at that position until I graduated. At the end of every meeting, we would throw open the windows of the Tower Room and “Sing from the Ramparts”, as it were. Many times, for hours. I rather imagine that we could be heard for literally miles around. Those were great and heady days as a young musicians at Central. Our faculty included one of the eminent choral conductors of the state, Dean Luther Spayde, and our band directors were Ken and Nancy Seward, whom we all considered somewhat the equivalent of direct descendants of the “Gods of Band Music on Mount Olympus” at the time.

I also was a member of a “social fraternity” on campus. And they were nice guys, but I was not so much a member as I was the “PR Guy” who always headed up the campaign and final rally for the fraternity’s candidate for Student Council President. My candidate always won. But . . don’t ask me to remember their names. Or sadly, the members. I don’t mean to disparage my association with them, but actually the only guys I remember were the other musicians in the group!

But I can recall events from three and a half years of Sinfonia. I suppose it’s because ALL of us had at least one thing in common. Obviously, our enthusiastic love for music and probably a somewhat distorted idea that we were destined to change the world or at least, add to it significantly. It WAS the 1960’s and “revolution” of all kinds was in the air.

On our first “married” Christmas, my wife paid all of $25 to give me a life membership in Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia. (I would imagine it’s a bit more in 2012.) And then, “Life” began to intercede. Army. Family. More school. Composition. Conducting. Ministry. Travel.

A few years after arriving at Lee University there was a move to start both a SAI and Phi Mu Alpha Chapter. Being, literally, the ONLY Sinfonian on the campus, I became the charter sponsor of the new chapter. However, as soon as other faculty members were inducted over the next several years, I passed the torch. Basically, I was on the road so much that it was virtually impossible to be at meetings, etc.

There’s that. And anyway, I’m a grown-up now.

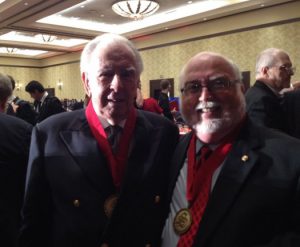

Last winter, however, a friend called about commissioning a fanfare for the upcoming PMA Convention and a larger work for the 2015 convention. He also indicated if I should come to the convention, something special was going to happen.

Now, I admit, getting to meet and talk with and eventually share induction into Sinfonia’s esteemed Alpha Alpha Chapter with Carlisle Floyd, the legendary American opera composer, was “special” enough for the weekend. Having the Signature Sinfonian Medallion presented to me was a totally unexpected honor. But all that wasn’t really the “special” event of the weekend.

The memorable peak of the weekend was actually hearing 800 young men sing out at the top of their lungs and radiate, through their enthusiastic love for music that, they too, even in this bleak, politically angry, saturated-with-hate world, believe they are destined to bring revolution through their art to a generation starving for grace in the human spirit. I was confronted by the same youthful ebullience that I had enthusiastically followed to my dreams 48 years ago, and the founding young men of Sinfonia had espoused nearly 50 years before that, in these youthful collegiate gentlemen.

So thank you, Men of Sinfonia, for reminding me of youthful exuberance, fanatical dedication, and all the wonderful times of college days in Beta Mu chapter, singing Sinfonian songs from the Tower Room, high above the campus. I had, in the fullness of “growing up”, forgotten one of the most exhilarating first steps of that life journey.

Thanks for stirring the memories.

***

10. ESSAY FACEBOOK, 2014 – ON CONDUCTING

I was gratified a few days ago when a couple of my students tagged me about their conversation concerning some of the Laban movements I have been inserting in the conducting lessons. The fact is, I don’t teach composition anymore – I seem to have my hands full with my young conductors. This is new territory for me. And my young conductors of late have been doing wonderful work around the country and even overseas, both in and out of school. Getting in good grad schools and good jobs. I’m very proud of all of them.

So what method of conducting do I teach? I don’t do methods, I teach people.

I teach the people whose artistic ideas have gotten me excited along the way.

I teach:

Hale Vandercook and Hubert Nutt

Rudoph Laban

Kenneth Seward

Russell Coleman

Robert Foster

Sarah McKoin

Dennis Fisher

Lowell Graham

Evan Feldman & a few others

(Who have no idea that I watch them conduct on the few videos

on the web and then use them for examples of clarity.)

TEDTALKS on conducting. Be choosey.

There are some basic “rules”, of course:

Have a “Belief System” concerning music. There are certain attributes of expression that always work. These have worked for centuries – will keep working after we’ve all turned to dust. Never approach the podium with an empty tool box.

STEAL! Steal from the best. Watch other conductors. Good and . . . not so good. You are never too old to learn. Or try something new. But be prudent. If the gesture is uncomfortable for you – it’s probably not FOR you. It looks better on the other guy.

Don’t look stupid. Get your nose out of the air. Look like the music. There are probably more elegant and aesthetically pleasing ways to say this, but if you don’t look like the music, what the heck are you doing up there, anyway. Amazingly enough, KNOWING the music helps this area. (There are numerous sub-sections to this rule.)

Don’t be too proud of yourself.

AND

Always go to the restroom before the concert, even if it’s only a trickle. The middle of the third movement of a six movement work is way too late to think about THAT! (There has to be at least one rule that even the dimmest of us can master.)

*****

10A. A CONDUCTORS RANT: OPINION ON NEW BAND MUSIC (NOVEMBER 2020)

This is just my personal opinion. I’m bored with a lot of young composers who write six to ten minutes of “mood music” that has no counterpoint, no forward direction and in most cases, simply wanders around in harmonic blandness demonstrating no imagination for even the simplest of any self-defined formal structure. I don’t expect Sonata Allegro form to have a rebirth, but please take me somewhere with some kind of musical reasoning apparent in construction. Give me a chance to teach my musicians about how to deal with moving lines, the weight of note values, the contours and plateaus of melodic and harmonic evolution.

Give me an experience that arrives somewhere. Anywhere. Please.

******

10B. MY PERSONAL GUIDE LINES AS A TEACHER/CONDUCTOR (Advice to young teachers)

ESTABLISH A PERSONAL BELIEF ABOUT MUSIC IN GENERAL

Identify those musical attributes you attain to as a musician and conductor. Three attributes influenced by Vandercook 1926 book entitled “Expression in music.”

ATTRIBUTE 1: ALL NOTES DO NOT WEIGH THE SAME.

Corollary: Smaller valued notes lead to larger notes.

Less significant notes lead to more significant notes.

“Leading” usually requires crescendo, creating forward motion.

ATTRIBUTE 2: ALL MUSIC MOVES FORWARD.

Corollary: Music moves forward point to point. Not note to note.

Makes us more aware of the destination of motives,

phrases, sections, etc.

ATTRIBUTE 3: LINES THAT ASCEND CRESCENDO, LINES THAT DESCEND DECRESCENDO.

Original corollary: Helping woodwinds understand performance of busy arpeggios in orchestral transcriptions for band.

Modern corollary: The contour of the line (any line) dictates its dynamic(s)

AND IN ADDITION TO THE ABOVE: I SHOULD, IN MATTERS OF EDUCATION OF MUSICIANS UNDER MY BATON

LEAD/GUIDE/MOTIVATE (Be in charge of the players’ and listeners’ experience)

FACILITATE THE EXPERIENCE (Make the musician players’ job easier)

ANIMATE AND PORTRAY THE SCORE (Become the music)

MOLD SYMBOLS INTO SOUNDS AND SHAPES (Turn the abstract into concrete sound)

PROVIDE A MEANINGFUL LEARNING EXPERIENCE

SOLVE PROBLEMS (Identify and solve problems quickly. Be articulate and informed, efficient and thorough.)

MAKE DECISIONS (Interpret. Have ideas. A wrong decision is better than NO decision.)

BRING ORDER TO THE PROCESS (It is better to have a plan and not need one, than to need a plan, and not have one!)

ESTABLISH A POSITIVE ENVIRONMENT IN WHICH TO MAKE MUSIC (A greenhouse for art.)

BECOME THE COMPOSER’S REPRESENTATIVE (Earn that right by study of composers musical traits.)

BECOME THE CONSCIENCE OF THE ENSEMBLE (Develop accountability through action.)

11. BOOK EXCERPTS

IN 2003, I, ALONG WITH TEN OTHER COMPOSERS WERE ASKED TO WRITE CHAPTERS FOR A BOOK ENTITLED “COMPOSERS ON COMPOSING FOR BAND”, EDITED BY MARK CAMPHOUSE AND PUBLISHED BY GIA, CHICAGO. EACH COMPOSER WAS ASKED TO ADDRESS SPECIFIC TOPICS. HERE IS AN UPDATED EDITED VERSION OF SOME OF THOSE TOPICS.

SINCE THERE MAY BE MATERIAL IN THIS CHAPTER THAT COULD HELP MUSIC STUDENTS IN RESEARCH, I HAVE INCLUDED THIS DRAFT OF THAT “HOLSINGER” CHAPTER FOR YOU. THIS WILL BE EASIER ON ME THAN ANSWERING MANY QUESTIONS VIA EMAIL.

******

- FIRST PERSON BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

My birthdate is December 26, 1945. By all indications, I was born in an unwed mothers home in Kansas City, Missouri. Early in 1946, I was adopted by Marvin and Hannah Holsinger, who lived in a small farm community 50 miles east of the city. Among the things my parents knew about my birth parents was that both were high school students from Iowa, and each came from musical families. This information made a lasting impact on my parents, and when I was not quite five years old, I began taking piano lessons from Mrs. Trenchard, the local piano teacher. My mother insistently declared that for the first year she had to “beat me to the piano”, and after that, she spent a lifetime, “beating me away from the piano”! I mention all this to, in some small measure, explain the seed of my musical fervor, which has nothing to do with deep seated hostility toward John Thompson, Book One. It just seems that music was the center of my life for as long as I can remember.

As an only child, growing up on a farm in Hardin, Missouri, was not a bad life. I had my dogs, my .22 rifle, and one heck of a vivid imagination. It wasn’t until I had children of my own that I encountered the “Sibling Zone”. I was alone and could be anything or anybody I could imagine. One day a cowboy, next day a soldier . . . Superman, able to leap tall buildings and jump off the garage roof, towel tied around the neck for lift, sailing thru the air . . . usually suffering the inevitable broken body part. Other than that occasional setback, life was great on the farm. As expected, I helped my Dad with fieldwork. Of course, he had to suffer the plight of having a son who had to have three or four “music breaks” a day. Whatever chore I was assigned was always subject to interruption as I left the tractor and scurried to the farmhouse to play piano for a half hour or so. He probably should have hired extra help.

I loved music. I sang myself to sleep every night. I took jazz lessons on the Hammond organ from the organist for the Kansas City Athletics. I knew how to “improvise” in Junior High. I was in every music and drama group in school. Everybody said I’d make a wonderful music teacher when I grew up and went to college. So proceeding on that assumption, I endeavored to grow up.

I’ve attended Central Methodist College (Now University) in Fayette, Missouri, Central Missouri State University (University of Central Missouri) in Warrensburg, and the University of Kansas at Lawrence. At the last two the study of composition was my primary goal. However, it was an incident at that first small college that set me on the course I travel today.

In the 1950’s and 60’s, Central Methodist College was a hotbed for music education graduates. Although very small, with fewer than 1000 students, the college seemed to produce an inordinate number of very good instrumental and vocal educators for the state’s public schools. Almost every music teacher I had in public school had been a graduate of CMC. Somewhere along the way, I just knew it was the place for me. I went to Central Methodist to become “the music teacher.”

However, I discovered one thing about my career choice very early in my education. In comparison to all my classmates, their desire to be a music teacher was CONSIDERABLY GREATER than my desire to be a music teacher. But, music was all I knew and, of course, everyone back home DID have my future all figured out. Who was I to argue? I was having a great time being a college guy, so why buck the system? In the spring of my junior year, everything changed.

Like a number of small colleges in the midwest, the Central Methodist Band and Choir always had a spring tour, usually consisting of seven days of travel with three concerts a day at schools or churches. One group headed east, the other west. In the fall of 1965, our band director announced that we would have a guest composer traveling with us on the upcoming spring tour. His name was Vaclav Nelhybel and he would be conducting two of his recent works, Trittico and Chorale. The pieces arrived. The music was big and brash, loud and gritty. They were vibrant and full of thunderings and poundings, and we couldn’t wait for this man to show up on our doorstep! My classmates and I were all young and egomaniacal in those days. The first thought in our collective mind was “we’ve hot players and we’re going to show this guy what music is all about!”

Two days before tour, Vaclav Nelhybel walked into our band hall, stepped on the podium, lifted his arms . . . As I watched that first slashing downbeat of the baton, I realized I didn’t have a clue what HIS music was all about. I had absolutely no idea how “personal” music could be. In that one electrifying instant, I saw brutality, beauty, angst, anguish, joy, triumph, sorrow, exhilaration, devastation, despair, hope, faith . . . all in the eyes of one man conducting HIS music. For seven days we rode the bus and played the schools. At the close of the final tour concert, I sat in the back of an empty stage and wept. I was overcome by the transformation I knew was happening in my life. I had now come face to face with my future. I wanted to be a composer.

The following week was spring break. I went home to the farm, set down at the piano and proceeded to work, morning, noon, and night writing my first composition. I don’t remember the exact day my mother ran screaming from the house, but nevertheless, at the end of the week, my first composition emerged; a work for band I entitled Prelude and Rondo. A few years later, it was to become my first published work.

In 1967, I graduated from Central Methodist and immediately moved to Central Missouri State to begin a masters degree. From that point, life seemed to gather that uncompromising acceleration none of us are ready for, but we all experience . . . I “joined” the army; I married; I won my first composition contest, sponsored by the Federation of Music Clubs of America. My wife and I moved to Europe where I was stationed in Germany; I won my second composition contest at Kent State University. I returned to civilian life and back to school. I played trumpet, keyboards and sang in a rock band for five years. (Baby #1) Several more of my compositions are published to good reviews. I teach high school music and I go back to school at the University of Kansas (Baby #2) and win my first of two Ostwald prize in composition. (Baby#3) I accepted Jesus Christ as my Savior, and I moved to Texas. (Contrary to some thinking in the Lone Star State, let me add that of the last two items, the latter is not necessarily a direct result of the first. I have it on good authority that God also recognizes the other 49 states!)

I know that, at this juncture, many are asking themselves, “Aren’t serious composers supposed to suffer more?” Let me point out that for the first seven and a half months we lived in Texas I worked as a laborer in a drapery factory cutting out blackout drape ten hours a day, six days a week. Every evening I would come home with my hands so swollen that it was impossible to play the piano. However, during that period, I composed The Deathtree for the U.S. Marine Band, which would later become the centerpiece of The Easter Symphony. I was also commissioned and wrote In the Spring, At the Time when Kings Go Off to War, which shortly thereafter, became my second winning entry in the American Bandmasters Ostwald Prize. (OK, it appears that even my suffering has gone well! So much for the “hard-knock” life.)

I spent 16 years at Shady Grove Church in Grand Prairie, Texas, in the center of the Dallas-Ft. Worth metroplex. During my tenure there, I served in many capacities as a music minister, however, for the most part, I was a composer in residence. I served a pastor who understood that my passion to compose was a ministry that extended beyond the walls of his church. Therefore, it was his heart to be my “patron” and help me succeed in that evocation.

[The past 22 years have been spent at Lee University as Conductor of the Wind Ensemble and teacher of conducting, composition, and orchestration.]

- THE CREATIVE PROCESS,

As a “maturing” composer, I realize that “personal emotion” is a primal factor in my output. I easily “wear my heart on my sleeve”, compose music that is experience motivated, and make no apologies for compositions that are written, expressly, to be “in your face.” I wish I was a glib and inspiring wordsmith, but I’m not. I speak best with music. I’m just a composer guy.

I don’t produce a lot of music in a year. It’s not that I’m a slow and meticulous composer, but rather, my output is a direct product of my lifestyle. I accept only three or four commissions a year, because I have only the months of July through December in which to write. Somewhere along the way, 30 or so years ago, I was invited to guest conduct an All-State Band. Up until that invitation, I had perhaps conducted a half dozen regional and local bands in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area. I’m not sure how it happened to this day, but suddenly I was considered a fairly adequate conductor/motivator. This newfound career became disproportionally time-consuming. From January to June, I find myself on the road Thursday thru Sunday conducting, Monday thru Wednesday I am teaching at the university. All the other days I like to spend time with my wife and family. Do you see the math problem here?

As with that very first composition written over spring break of 1966, some things have not changed. I am basically a “binge” composer. Whereas many composers set aside that special time of the day when they are most apt to feel the muse rising, I, on the other hand, grab any chance I can get and then “go around the clock.” Music is easy. When it’s there, it simply pours out. This is not to say that I don’t have a “process”. I do. But I have also always had a good intuition about the movement of music. In fact, that intuition was probably the greatest detriment to my composition study as a young man. Many times, to the consternation of my teachers, I tended to leap over the process and depend on my intuitive gifting to complete the work. Basically I had the ability to make my music sound like, say Stravinsky, without really understanding the specific principle or craft of composition that Stravinsky represented at any given juncture of his career. I could imitate, without being able to offer explanation. Why some of my teachers just didn’t kill me on the spot still begs explanation!

So what is my process? At its inception, it is a “visual” process. I need a “picture” to paint. This explains why I write very little absolute music, but rather find myself exploring “story” music; writing compositions that depend on “word painting” even when no text appears in the finished product. I need a title before beginning a piece. I knew the story line for To Tame the Perilous Skies for weeks. It was intended to be a composition celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, but until the actual title was birthed, no note was put on the page. Silly quirk.

I wised up about studying the compositional process and using the intuitive gift to my advantage. Consider again, Stravinsky. Here was a man who never settled for the “status quo.” He is an example to my students of a composer who watched and examined as the winds of change blew through a half century of compositional exploration. He carved, he dissected, he pulled aspects from each “process” that sped by, and he put them in his own personal compositional toolbox. And then, after they all rattled around for a time, he pulled them out, he molded them to his specific compositional genius, and suddenly his music was old and new at the same time. The label may have said “atonal”, but the flavor was Stravinsky. The process might be “serial”, but the essence was first and foremost “Stravinsky”!

I, as a student of composition, learned an important lesson studying the result of that evolution. I believe, over the past 45 years, I have managed to combine chosen concepts of the craft of composition with the limitlessness of intuition and establish a “style” of writing that fits my personal perspective of what music should be.

I compose at the piano, at the keyboard and at the computer. My writing, for the most part, is linear.

I have had two great teachers of composition. I say “great” not because they were world renowned, but rather because they were EXACTLY the teacher I needed at the time I studied with each of them. The first was a man named Donald Bohlen, a student of Ross Lee Finney at Michigan, and at the time I met him, a “die hard” serialist! He was my composition instructor at Central Missouri State. To say that we were at opposite poles of the musical spectrum would be grossly understating the case. I learned more from this man in nine months than I had in the previous four years of college! He opened my ears and eyes to a 20th century of new sounds and compositional methods I had no idea even existed, much less an understanding of how they worked. Donald Bohlen’s influence is directly responsible for my becoming a linear composer rather than a vertical composer.

The second great teacher I had was Charles Hoag, Professor of Composition at the University of Kansas. From Donald Bohlen and Charles Hoag I learned that, regardless of the process I choose to utilize in my composition, that process must be DEFENDABLE. At any given point, one must be able to identify and trace the development of any single idea or flow of idea, but from Charles Hoag, I learned a very special lesson. Hoag taught me that I need not be ashamed of the choices I make. We are all bits and pieces of every composer, teacher, mentor and musician with which we have associated. However, we do not need to be carbon copies of anyone. No matter what the process we choose, whether we are conservative, radical, or somewhere in between, it is OK to have a PERSONAL voice in the process. I am aware that even if I chose to compose in the most mathematically intricate synthesis dealing with structure, pitch density, registral display and timbrel selection, that I would also be cognizant that it was a “personal” decision and it was MY voice that said, “I have decided this is the way it is going to be….”

Back to more practical matters. I have used Finale Software, MAC version, for a long time. My serial number is VERY small. When I started using the software package, the manuals weighed 14 pounds! The screen on my original Macintosh Classic appeared to be only about six inches square. (I spent more time waiting for “redraw” than breathing.) I probably only use 60% of the software’s capabilities, but what I do use, I use very well! Just call me “Mr. Computer Whiz.”

Working the DVD in the den is still a mystery.

- PERSONAL THOUGHTS ON ORCHESTRATION

It is obvious to me that orchestration is as much a product of the composer’s style as are the choices he or she makes compositionally. In that regard, I consider myself a fairly “white bread” orchestrator!

I am so impressed with people who really deal in the color palette available. Philip Spark’s use of muted brass in his second Dance Movement is incredible. I very rarely think of using mutes. Fellow composer Jim Barnes, who I consider a master instrumentationalist, is constantly aware of the instrumental color spectrum he deals with. He is consummately mindful of the the soloistic qualities of each instrument. The scores of his major works reverberate with vivid timbrel hues. I hardly ever write solos or think about soloistic qualities. Mark Camphouse’s instrumentation choices always seem to forge a grand and glorious, almost Mahler-esque orchestral canvas. I think we’re fortunate he choose to compose for bands rather than orchestra!

Instrumental color is as much a signature of band composers as is their content. Let’s face it, Percy Grainger SOUNDS like Percy Grainger. There is a distinctive quality in his instrumental choices that, in combination with his musical style, sets his music apart. No one scored four-part horn sections better than Claude T. Smith. I’m not sure what he did, but his horn writing always sounded different than anybody else’s horn writing. That particular sound became just as much a musical signature as his whimsically notorious use of the 7/8 measure. (I can’t help but think that Claude was amused at the band world’s almost “mystical cult worship” of an asymmetrical measure.)

And even though at times, I wish my orchestrations were ripe with refined timbrel explorations, I know that what I do is exactly what my music demands. The choices I make are a direct product of the music I write. My high woodwind parts are always extreme, because I want edge and enunciation in their lines. The doublings I use are not meant to acoustically produce new sound spectrums. They are employed to DOMINATE the spectrum. I am aware that my music is very mid-voiced, therefore more and more, I score for only one or two F Horn lines. I more often than not, double my horns with trumpets, rather than alto saxes, because I want that brassy edge to be paramount. The saxophones, over the years, have become the section I use as the “engine” of my orchestration, considering their flexibility and brashness. I also consider the versatility of the instruments. My clarinets can be penetrating and edgy or full and reverent. My reviewers refer to “no mercy” horn lines, and yet at times, I ask those same players to be the timbre of weeping.

One aspect of my orchestration has very little to do with color. It has everything to do with the individual musician seated in the ensemble. When Vaclav Nehlybel conducted the Central Methodist Band, I was a baritone player in the ensemble. (I was never good enough to be classified a “euphonium” player!) One of the dynamics of that meeting was that I had a great part to perform in the compositions. In fact, it seemed that everyone in the band had important lines to play. No one seemed to think of themselves as “filler” material. I was always very aware of that feeling of “essentialness” when I begin writing and scoring music as a young composer. In an Instrumentalist review of one of my early works, Hopak Raskolniki, John Paynter stated, “Every player has an exciting part to play.” The desire that every musician involved feel that he or she was important to that performance, has really been an influence in my writing and scoring for a great many years. One of my pet exhortations is, “when the piece is over, you should to feel like you’ve been somewhere!” Every musician needs to feel like a vital cog in the machinery of a performance.

Most of my instrumentation choices over the years have probably been more the product of intuition than learnedness. Consider again my first composition, Prelude and Rondo. After finishing the music, I was faced with the daunting task of scoring it for band. So I bought some ready-made-band-score-paper, which in itself was a bit unnerving. (What the heck is a basset horn? I scratched that one off.) It was likely at about that same moment I realized that I hadn’t really paid all that much attention to Professor Anderson in orchestration class. But then again, we didn’t spend a great deal of time with “band” instruments in class. After all, here it was, 1965, and it was obvious to me that Kent Kennan was unaware that the saxophone had been invented and was in everyday use! The book only listed about 12 percussion instruments, including the flexatone, which was there only because it appeared in both a Khachaturian piano concerto and Schoenberg’s Opus 31 Variations. Not necessarily a ringing endorsement! What my instrumental choices really had to draw from were the sounds I had heard while setting in a band for the past ten years. So I just started fitting music to the family of instruments I felt best portrayed the character of each particular section. My moment of confusion came with the F horns. Do they go up a fifth, or down a fourth? Obviously, not being the sharpest knife in the drawer, I decided to write the horns wherever they fit the best, so as not to crowd the music above and below them on the ready-made-band-paper staves.

Since confession is good for the soul, I admit in writing, to my ignorance some 30 years ago, that yes, many of the measures of F Horn in Prelude and Rondo are actually transposed to the wrong octave. Of course, when conductors enthusiastically expound on the “wonderful” horn-writing in said piece, I am always quick to reply, “What can I say…..stroke of genius, I suppose…” Perhaps ignorance IS bliss.

I probably shouldn’t leave this subject before discussing my percussion writing, which to many, seems to be one of the hallmarks of my compositions. Again, we’re talking accidental fame! Once, while visiting Frances McBeth at his home, we were setting around the front room sharing stories. Dr. McBeth begin to recount an incident with his composition class. He went on describing how many of his young composers insisted on waiting until their pieces were completed before even considering writing percussion into the score. “David,” he said to me, “I told them how foolish that was….I said, only BAD COMPOSERS would do such a thing!” You know what’s coming, don’t you? For the slightest of split-seconds, Frances McBeth was almost speechless, as I indicated that that was exactly the process I utilized in my own work. Again, however, my percussion scoring is a direct product of my compositional process. I write many linear lines containing diverse rhythmic elements, all which run somewhat amuck, but fortunately in the same direction most of the time. I need to “live” with the density of this rhythmic collage in order to really understand what the percussion underpinning of the music should be. Before moving to the computer age, there were times when I had inked the score and copied all the parts before I was ready to add that final layer of percussion to the fabric of the composition.

I love percussion. I consider them vitally important to the energy of my works. My mallet writing directly affects the enunciation of my woodwinds. My timpani parts are notorious for being almost scalar in content. I think timpani players deserve more than four pitches per composition! (What are those tuning pedals for, anyway?) My auxiliary writing is meant to enhance the tonal choices that exist. I spend hours in “rock’n roll” pro shops, just fooling with all kinds of noisemakers to see if there is a new addition that will fit my particular compositional palette. The percussion section is the only family of instruments still growing and developing. As long as one can find two different rocks to hit together, we will always have a evolving and diverse list of ingredients available for the percussion texture.